Tabula Peutingeriana – Einzelanzeige

| Toponym TP (aufgelöst): | Flumen Ganges |

| Name (modern): | Ganges |

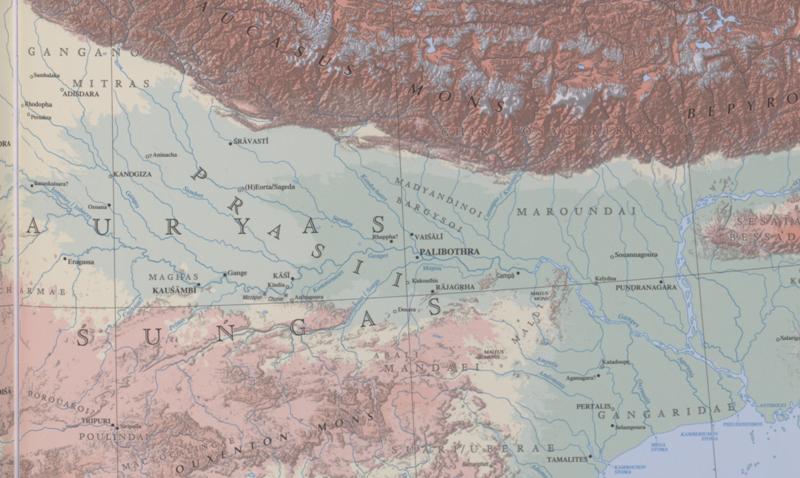

| Bild: |  Zum Bildausschnitt auf der gesamten TP |

| Toponym vorher | |

| Toponym nachher | |

| Alternatives Bild | --- |

| Bild (Barrington 2000) |

|

| Bild (Scheyb 1753) | --- |

| Bild (Welser 1598) | --- |

| Bild (MSI 2025) | --- |

| Pleiades: | https://pleiades.stoa.org/places/59822 |

| Großraum: | Indien |

| Toponym Typus: | Fluss |

| Planquadrat: | 11B2 + 11B5 |

| Farbe des Toponyms: | rot |

| Vignette Typus : | --- |

| Itinerar (ed. Cuntz): |

|

| Alternativer Name (Lexika): |

|

| RE: | Ganges [3] - https://elexikon.ch/RE/VII,1_705.png |

| Barrington Atlas: | Ganges fl. (6 E4) |

| TIR / TIB /sonstiges: |

|

| Miller: | Fl` Ganges |

| Levi: |

|

| Ravennat: | Ganges (p. 17.15) |

| Ptolemaios (ed. Stückelberger / Grasshoff): |

|

| Plinius: |

|

| Strabo: |

|

| Autor (Hellenismus / Späte Republik): |

|

| Datierung des Toponyms auf der TP: | --- |

| Begründung zur Datierung: |

|

| Kommentar zum Toponym: |

Kommentar (Talbert): |

| Literatur: |

Miller, Itineraria, Sp. 846f.; |

| Letzte Bearbeitung: | 04.11.2025 15:21 |

Cite this page:

https://www1.ku.de/ggf/ag/tabula_peutingeriana/einzelanzeige.php?id=2704 [zuletzt aufgerufen am 04.03.2026]