Tabula Peutingeriana – Einzelanzeige

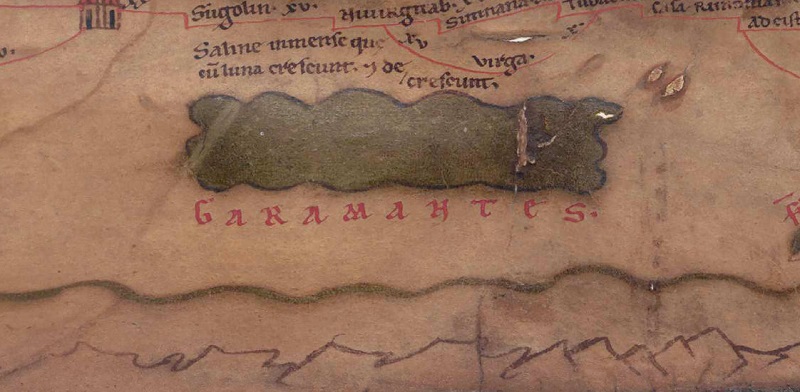

| Toponym TP (aufgelöst): | Garamantes |

| Name (modern): |

|

| Bild: |  Zum Bildausschnitt auf der gesamten TP |

| Toponym vorher | |

| Toponym nachher | |

| Alternatives Bild | --- |

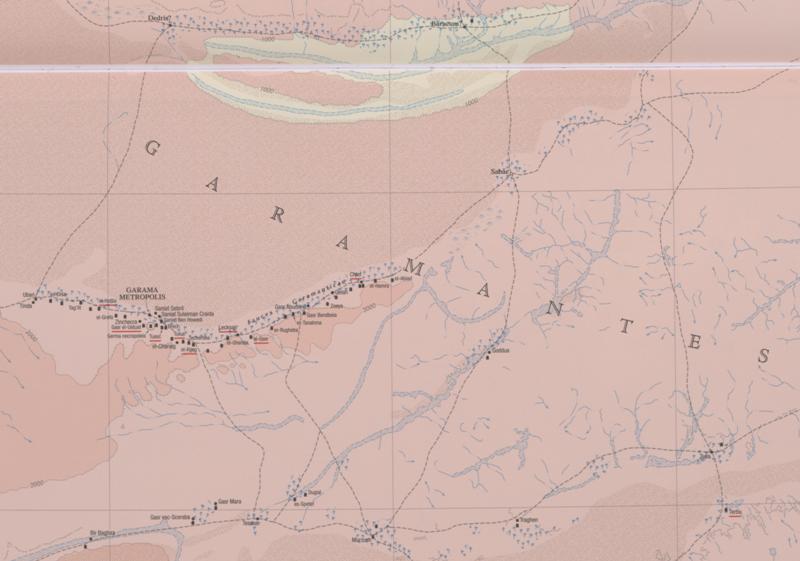

| Bild (Barrington 2000) |

|

| Bild (Scheyb 1753) | --- |

| Bild (Welser 1598) | --- |

| Bild (MSI 2025) | --- |

| Pleiades: | https://pleiades.stoa.org/places/354116 |

| Großraum: | Africa Proconsularis |

| Toponym Typus: | Ethnikon |

| Planquadrat: | 6C4 |

| Farbe des Toponyms: | rot |

| Vignette Typus : | --- |

| Itinerar (ed. Cuntz): |

|

| Alternativer Name (Lexika): | Garamantes (DNP) |

| RE: | Garamantes |

| Barrington Atlas: | Garamantes (36 C4) |

| TIR / TIB /sonstiges: |

|

| Miller: | Garamantes |

| Levi: |

|

| Ravennat: | Ethyopia Garamantium (p. 2,66f.; 37.01; 43.42f.), Ethyopia Garamantium, qui et Asbyste dicitur (p. 3 |

| Ptolemaios (ed. Stückelberger / Grasshoff): | Γαράμαντες (1,8,5; 1,8,6; 1,9,8; 1,9,9; 1,11,4; 1,11,5; 1,12,1; 4,6,16; 4,6,18) |

| Plinius: |

|

| Strabo: |

|

| Autor (Hellenismus / Späte Republik): |

|

| Datierung des Toponyms auf der TP: | frühe Kaiserzeit (einschließlich Flavier) |

| Begründung zur Datierung: | Die Garamanten sind von der Klassik bis in die Spätantike in der antiken Literatur bezeugt. In der frühen Kaiserzeit wurden sie (ebenso wie die Nasamonen und Gätuler) zu einem bedrohlichen Machtfaktor für Rom in Afrika, dürften in dieser Zeit also durch die Feldzüge unter Augustus und die entsprechende zeitgenössische Propaganda (Verg. Aen. 6, 794f.: „Er [sc. Augustus] dehnt sein Reich, wo fern Garamanten und Inder wohnen“) ins Bewusstsein der antiken Mittelmeerwelt gelangt sein. |

| Kommentar zum Toponym: |

Die Garamanten werden in den antiken und mittelalterlichen Quellen als bedeutendes, in der libyschen Sahara bzw. jenseits von vasta deserta (Plin. nat. 5, 26) oder „hinter den Wüsten“ (Mart. Cap. 6, 671) lebendes Volk bzw. eine Stammeskonföderation (vgl. Orosius) dargestellt: So zählt Plinius mehr als 25 Stämme mit ihren Städten auf (Plin. nat. 5, 37). Als bedeutendster Ort der Garamanten gilt Garama (vgl. z.B. Plin. nat. 5, 36: clarissium Garama, caput Garamantum; Ptol. 4, 6, 30: Γαράμη μητρόπολις; Isid. etym. 9, 5, 13: Garama), die Ebstorfer Weltkarte (48/8: Carama c.) und die Hereford Map (mit abweichender Schreibung: Gamara civitas). Gelegentlich werden die Garamanten mit Ammon und der Ammon-Oase (Siwa) in Verbindung gebracht (Verg. Aen. 1, 28; 4, 198: Garamantis; Schol. Serv. Aen. 4, 198). Nach Orosius bevölkern die Garamanten den Raum zwischen den Arae Philaenorum und dem "südlichen Ozean" (oceanus meridianus) bzw. "Aethiopicus oceanus / oceanus Aethiopicus". Auf Grund der Lage eines Teil ihrer Wohnsitze im extremen Süden werden die Garamantes häufig gemeinsam mit den Aethiopes aufgelistet (Isid. etym. 9, 2, 125; 14, 5.6. 13; davon abhängig Hrabanus Maurus, De univ. 12, 4; 16, 2) und auch mit ihnen zu einer ethnischen Einheit verschmolzen (Solin. 30, 2f.: Garamantici Aethiopes; Cosm. Rav. 136, 3; 138, 11: Aethiopia Garamantium; Ebstorfer Weltkarte: Garamantes Ethyopes); auf der Hereford Map werden sie gemeinsam mit anderen Völkerschaften im libyschen Teil Afrikas aufgelistet: Hic Barbari, Getuli, Natabres et Garamantes habitant. Laut Orosius (Hist. adv. pag. 1, 2, 90) sind sie in der Nähe eines Salzsees verortet, der wohl mit dem auf der Tabula Peutingeriana "oberhalb" der Garamanten eingetragenen Gewässer gleichzusetzen ist. Die Beischrift saline immense ... findet sich in ähnlichem Wortlaut auch auf der Ebstorfer Weltkarte. Die antike Historiographie kennt mehrere römische Kampagnen gegen die Garamanten: Unter Augustus, wohl 21/20 v.Chr., führte L. Cornelius Balbus, der Proconsul von Africa einen Feldzug gegen die Garamanten und präsentierte in seinem Triumphzug ex Africa (19 v.Chr.) Bilder mit namentlicher Nennung der eroberten Ortschaften (Plin. nat. 5, 36. 37; Solin. 29, 7), worauf eine Legende auf der Ebstorfer Weltkarte (41/27) hinweist: Garamantes Ethyopes Has Cornelius Balbus ditioni Romane subegit. Einen zweiten Sieg über sie in augusteischer Zeit bezeugt Flor. epit. 4, 12, 41. In tiberianischer Zeit unterstützten die Garamanten den Tacfarinas-Aufstand gegen die römische Herrschaft (Tac. ann. 3, 74; 4, 23), nach dessen Scheitern sie eine Friedensgesandtschaft nach Rom schickten (Tac. ann. 4, 26). 70 n.Chr. fielen die Garamanten in Tripolitanien ein und verwüsteten das Gebiet um Leptis Magna (Plin. nat. 5, 38; Tac. hist. 4, 50). Spätere militärische Kampagnen gegen sie erwähnt Marinos, der Gewährsmann des Ptolemaios (Ptol. 1. 8, 5: Γαράμαντες). Die Garamanten waren in der römischen Welt also eine bekannte ethnische und politische Größe, daher zählt das Wüstenvolk am Südrand der Oikumene in der Antike und auf der antiken Literatur aufbauend auch zum festen geographischen Wissenskanon des Mittelalters, sie sind das „klassische“ Volk in der Sahara und daher in zahlreichen Texten und Karten der Antike und des Mittelalters präsent. Auch durch archäologische und architektonische Zeugnisse sowie durch Felszeichnungen sind die Garamanten bezeugt (vgl. die Publikationen von Ruprechtsberger). - Vgl. zu Saline inmense que cū luna crescunt· et decrescunt·, Nesamones·), Gaetuli) und MVSVLAMIORVM·. |

| Literatur: |

Miller, Itineraria, Sp. 948; |

| Letzte Bearbeitung: | 31.12.2024 00:15 |

Cite this page:

https://www1.ku.de/ggf/ag/tabula_peutingeriana/einzelanzeige.php?id=2222 [zuletzt aufgerufen am 31.12.2025]